Before I became a teaching fellow and stipends became my main source of income, I worked in various jobs across the campus. I had been the assistant director of undergraduate admissions before returning to school, and so, my foot was in the door for administrative jobs I wouldn't have been considered for, otherwise.

For instance, I was the director of a summer program for African and Native American students from rural or small-town environments. My university was a medium-sized institution of approximately 16,000 undergraduates, and our research had shown that students from the countryside and micro-urban communities had the most trouble adjusting to the large, impersonal campus. Strikingly, this was as true for students with SAT scores above 1300 as it was for those below 1130, the university average at the time. They cited a lack of connection to the campus and feelings of alienation in their exit interviews. For students withdrawing with passing grades, those reasons were cited above all others, and they were pretty much universal, cutting across race, gender, and class. But they were particularly true for small town folk and even more so for African Americans and Native Americans. Consequently -- and by "consequently," I mean, "after losing a law suit" -- the university created the program that I ended up directing.

Part of the students' orientation program included a tour of the student health facilities and part of that tour was a frank discussion with the sexual education director, the sweetest, kindest grandmotherly woman you could ever hope to lay eyes upon. A woman on a mission, she was frank and knowledgeable and eager to pass along her education. Her visage was as disarming as her delivery was blunt: It was like having a nice, cozy tea with an tender and kind octogenarian, and in the course of events, having the conversation turn in such a way that you find yourself being to.d to "back up out of there" if during cunnilingus you discovered your lap partner had vaginal warts. (And, yes, that actually occured.) She was good.

She kept it light and informative, and she drew the students out by awarding prizes to the ones who asked honest questions and the ones who answered her questions honestly. As befitting the occasion, usually, her prizes were sex-oriented objects, like condoms and lubricants and vaginal gels and "Wrap that Rascal" t-shirts, things like that.

Once after showing one incoming group how, with just a few quick cuts here and there, they could turn a condom into a makeshift dental dam, she lauched into a lecture on safe oral sex, telling my charges that licking latex, although necessary, didn't have to be a flavorless, pleasureless chore for the licker, that with flavored gels, even the person on the tongued end of the equation could have a little fun. My students were rapt, writing down her advice like it was gospel, taking notes as if salvation depended on it. Every head was down, every pen was up, scratching her Truth into their notebooks. Then, up went the hand of a kid, an African American kid, from a town with "Crossroad" in its name (and it was as apt a description of the community then, as it was a hundred years ago when it was named).

"Yes," said Mother Sex-Ed.

"Do any of them gels come in a fried chicken flavor?"

For that, he got a t-shirt, a "No," in reply, and a warning against trying to create one.

He also got to see his director shoot coffee from his nose.

Anyway,

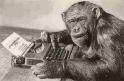

that long introduction exists to explain why I thought of that kid when I saw this.